OTHER COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED MEDICAL

CONDITIONS IN REFUGEE PATIENTS

COMMON

GASTROINTESTINAL

PARASITES

Gastrointestinal parasites are a lot more common in refugee patients than in the regular Canadian population. This is especially true for children from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (DeVetten et al., 2017). While we recommend against routine screening of newly arrived refugees for GI parasites, testing should be considered in any refugee patient with GI symptoms, unexplained anemia or eosinophilia

(mainly helminths, rarely protozoa). We also recommend testing for parasites in all refugee children with growth problems. While the clinical manifestations of each GI parasite are not covered here, keep in mind that they can cause a variety of symptoms (often mild) that can mimic other common conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, dyspepsia or hemorrhoids (pinworm).

Traditional Ova & Parasites

stool testing is not a sensitive diagnostic method, and thus repeat testing (at least 3) is recommended if a parasitic infection is suspected. In contrast, the Protozoal Screen

done at Calgary Laboratory Services is a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that is very sensitive and can accurately detect Giardia

species, Cryptosporidium

species and Entamoeba histolytica

with a single sample. Repeat testing is thus not necessary for this test. Unless the indication for testing is eosinophilia (in which case only Ova & Parasites is recommended), we usually order both screening tests when investigating a patient for potential GI parasites.

The recommended first-line treatments (Tx) for the most common GI parasites found in Canadian refugee patients (for

uncomplicated intestinal infections only) as well as the recommended tests-of-cure (TOC) can be found below:

HELMINTHS

PROTOZOANS

Additional comments:

- In Calgary, praziquantel and paromomycin can usually be found at Lukes Drug Mart in Bridgeland.

- Only our preferred first-line treatments are listed above. If these regimens fail to eradicate the GI parasite in question, a referral to an Infectious Diseases specialist is suggested (The Tropical Infectious Diseases Clinics Calgary).

Refer to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website

for more information on parasitic diseases.

Refer to the Drugs for Parasitic Infections guidelines

from the Medical Letter for additional treatment recommendations.

DYSPEPSIA AND

HELICOBACTER PYLORI

H. pylori

is very common in patients from developing nations. Therefore, it is often diagnosed when investigating refugee patients with dyspepsia. Refugee patients often complain of symptoms of dyspepsia (postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain/burning), but different cultures might use various terms and expressions to refer to these symptoms, such as “heat” or “noise” in the abdomen. It is often difficult to differentiate between constipation symptoms and dyspepsia in some refugee patients. Parasites such as hookworms, strongyloides, giardia and Dientamoeba fragilis

can sometimes cause symptoms that might be mistaken for dyspepsia and should be considered in refugee patients with persistent upper GI symptoms.

The “alarm features” for dyspepsia that warrant endoscopy are the same in refugee patients as for the rest of the population: onset at age ≥60, weight loss, anemia, iron deficiency, dysphagia, vomiting, palpable mass or lymphadenopathy,

and family history of upper gastrointestinal cancer.

DIAGNOSIS

Unless there is a clear indication for endoscopy, we first test all refugee patients with dyspepsia for

H. pylori

and treat if positive. In Calgary, the urea breath test (UBT) has been replaced by the

stool antigen test as the first-line diagnostic test for

H. pylori. Since patients will already be collecting a stool sample, it is reasonable to also order a stool Ova & Parasites and Protozoal Screen (PCR) in order to rule out parasites as a potential etiology (do not forget to fill out the

CLS Stool & Parasite History Form when ordering these tests).

While we often test adults who present with any GI complaint for H. pylori, testing in children

should only be considered in patients with clear symptoms suggesting peptic ulcer disease

or with refractory unexplained iron deficiency anemia. This is because H. pylori

infections in children without PUD rarely give rise to symptoms, and testing is thus not

recommended in children with functional abdominal pain disorders (Jones et al., 2017).

When ordering a H. pylori

stool antigen test, patients should be told to avoid the following medications prior to collecting the sample:

- Proton pump inhibitors: 14 days

- Antibiotics: 28 days

- Bismuth preparations (Peptol Bismol): 14 days

TREATMENT

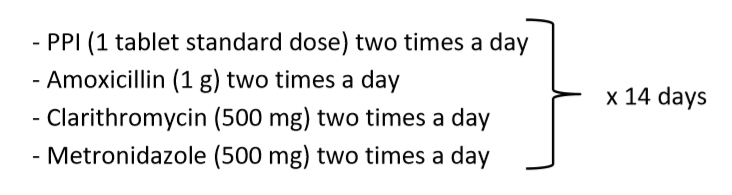

Due to increasing resistance, quadruple therapy is now recommended as first-line treatment for

H. pylori. Because it is less complicated than the other first-line regimen (Bismuth Quadruple regimen), we prefer the CLAMET Quadruple regimen in refugee patients*:

* We recommend prescribing H. pylori

regimens in blister packs (request it on the prescription) to improve adherence.

TEST-OF-CURE

We recommend performing a test-of-cure only in patients who are still symptomatic after treatment. In these cases, a repeat stool antigen test should be done >4 weeks after completion of treatment. H. pylori

is becoming more and more resistant (especially to clarithromycin) and often requires a second (Bismuth Quadruple Regimen)

or third regimen (Levofloxacin-based Regimen)

before being eradicated.

- If

H. pylori

is not identified as the cause of the patient’s dyspepsia or if treating the infection does not resolve the symptoms, refer to the Calgary Zone Primary Care Network

Enhanced Primary Care Pathway for Dyspepsia for a stepwise approach to dyspepsia*.

* The flow diagram on page 4 is especially useful. Since H. pylori is so prevalent in refugee patients, we tend to do step 4 (H. pylori test-and-treat) before step 3 (Baseline investigations) in this population. - Also refer to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) 2017 joint guidelines on dyspepsia for more evidence-based recommendations.

FEMALE GENITAL

MUTILATION

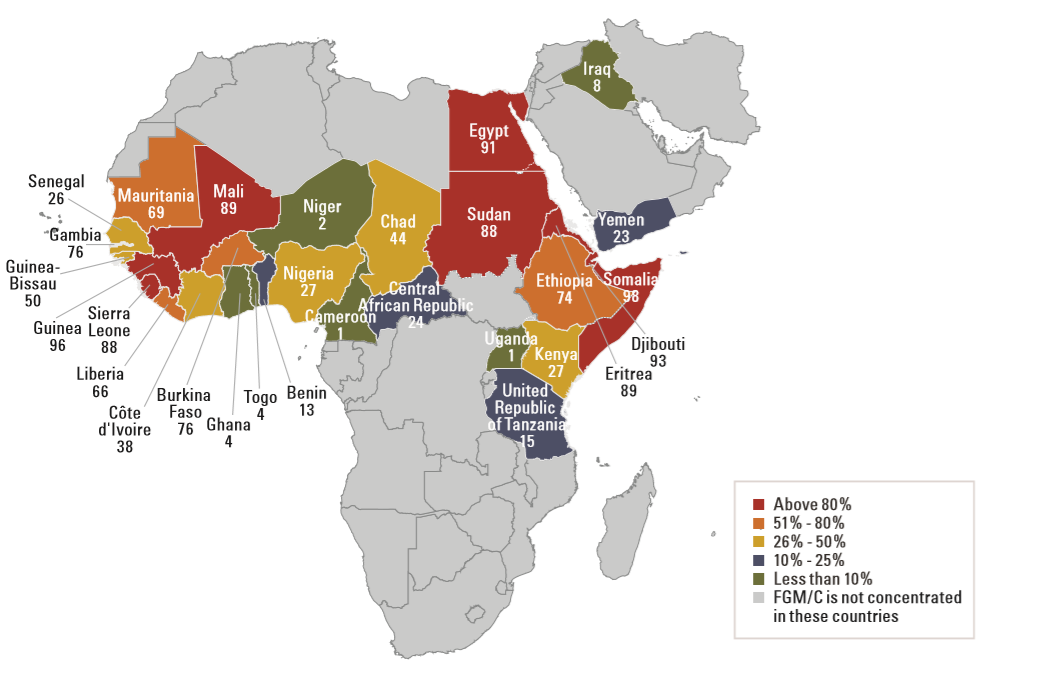

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also called female genital cutting or circumcision, is the partial or complete removal of a girl’s external genitals. This cultural practice is based on various traditions and beliefs (e.g prepares a girl for adulthood, preserves virginity before marriage, facilitates cleanliness) and has no known medical benefits. FGM is typically performed before the age of 15, but in some countries, it is often practiced on girls <5 years of age. FGM is a criminal offence in Canada and has been banned by the United Nations. It is mainly practiced in Africa and in the Middle East:

Map from Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change

(Unicef, 2013).

Physicians seeing refugees from countries where FGM is practiced should be aware of the potential associated complications/symptoms and be able to identify FGM on physical examination.

CHRONIC COMPLICATIONS

FGM is associated with multiple chronic complications including the following: anorgasmia, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, bacterial vaginosis, lower abdominal, vaginal and vulvar pain, dysmenorrhea, vaginal stenosis, chronic UTI. FGM is also associated with obstetrical complications, and can have long-term psychological impacts.

FGM CLASSIFICATION

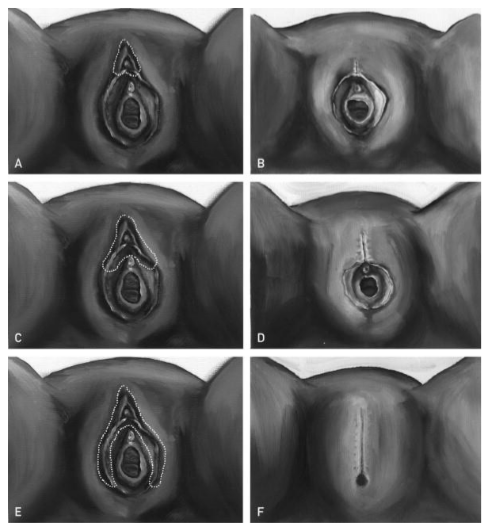

FGM can be easily missed on physical exam. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified FGM into 4 types:

Image from Female genital cutting: an evidence-based approach to clinical management for the primary care physician

(Hearst et Molnar, 2013).

Type I —

Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce (clitoridectomy)

Type II —

Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)

Type III — Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation)

+ Type IV —

All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization

SCREENING

While there is currently no evidence supporting routine screening for FGM in asymptomatic patients, screening should be considered for the following patients:

- Prenatal or antenatal patients (in preparation for delivery)

- Patients who will undergo a gynecological procedure (such as a Pap test)

- Any female patient who is from a country where FGM is performed and who has one of the complications/symptoms listed above

Screening for FGM should be done in a respectful and culturally sensitive manner. The word “circumcision” is preferred to “mutilation” when asking patients about FGM. The patient should be asked about her circumcision history (where, when, how) and about her beliefs regarding FGM. The physician should also inquire about potential physical and psychological symptoms related to the circumcision. An external genital exam should be offered to patients with a history of female circumcision in order to classify the type of FGM and guide further management.

Once a trusting therapeutic relationship has been established, physicians should also consider raising this topic with parents of young girls coming from countries with a high prevalence of FGM. These patients should be educated about the Canadian laws relating to FGM. They should know that sending their daughter away to be circumcised in another country is also a criminal offence.

MANAGEMENT

Patients with FGM who have any associated complication/symptom or who are potentially interested in a defibulation (surgical opening of the labia) should be offered a Gynecology referral. This is especially important if the patient is pregnant or planning a pregnancy (defibulation can be done ante or intrapartum). Patients under the age of 16 should be referred to Pediatric Gynecology.

For additional information on the assessment and screening of FGM, please refer to the Caring for Kids New to Canada

website.

HEARING LOSS

Hearing loss is a condition that is commonly encountered in refugee patients (both children and adults). Because most refugee children will not have received hearing screening in their country of origin, physicians should promptly order a hearing screen for any child with hearing concerns or language delay.

Hearing tests and hearing aids are covered by the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) for refugees. We usually refer our patients to one of the Pindrop

clinics in Calgary for hearing assessments. We have found that these clinics usually help patients who require hearing aids obtain IFHP coverage for the devices.

Patients can also be referred to the

Richmond Road Diagnostic and Treatment Centre for their hearing assessment. In Calgary, children with abnormal hearing test results should then be referred to the Alberta Children’s Hospital Hearing Clinic.

- For additional information on hearing screening in refugee children, refer to the Caring for Kids New to Canada website.

HEMATURIA

Hematuria is a common finding in our refugee patients. While we do not recommend routine urinalyses (UA) in asymptomatic patients, we regularly discover microscopic hematuria in patients tested for clinical reasons. In young healthy patients, a cause is often not identified. While our approach to hematuria in refugee patients is similar to the approach for the general population, a few additional elements (such as schistosoma and tuberculosis) have to be considered in this population. Microscopic hematuria is defined as >3 RBCs/high-power field on urine microscopy.

The following is our recommended approach

for refugee patients who are found to have microscopic hematuria. This approach applies mainly to adult patients.

1. Rule out schistosomiasis

Make sure schistosomiasis has already been ruled out as part of the initial screening tests in refugee patients from an endemic country (see Appendix A4). If not, then a schistosoma serology should be ordered. Patients with schistosomiasis and concomitant microscopic hematuria should be treated first before repeating the UA (wait at least 1 month after treatment). If microscopic hematuria is still found on the repeat UA, it is reasonable to re-treat the patient with a second dose of praziquantel since a single dose does not always kill all the adult worms. If microscopic hematuria is still present 1 month after the second praziquantel dose, the patient should then be investigated for another cause of hematuria.

2. Complete the history

Patients should be asked about any history of macroscopic hematuria* (red or brown urine) and/or blood clots, flank pain, pyuria, dysuria, increased urinary frequency, and urinary retention. Inquire about any past or current smoking history. Ask about any familial or personal history of bleeding disorders and make sure sickle cell has already been ruled out as part of the initial screening process (since both the disease and the trait can cause hematuria). A sexual history should also be performed to assess the risk of STI.

Female patients should also be asked if they had their period during or right before the urine test was performed. Patients should also be asked about any recent history of vigorous exercise or trauma. In these cases, a UA should be repeated with clear instructions: at least a few days before or after the patient’s period, not after any physical exercise, and at least a few weeks after any trauma.

* In patients with macroscopic hematuria, the following steps can still be followed, but a Urology referral should be requested right away.

3. Investigate common causes

In patients with microscopic hematuria, order the following tests:

- Repeat UA (to see if the hematuria is transient or persistent*)

- Urine culture & sensitivity and chlamydia/gonorrhea NAAT (if not already done) and treat if positive and repeat UA 6 weeks later

- Serum creatinine levels**

- Urine microalbumin test**

- Renal and bladder ultrasound

* Both cases should still be investigated, but this can give a clue about the underlying etiology.

** Proteinuria, elevated serum creatinine levels, RBC casts or dysmorphic RBCs on microscopy, hypertension, or "cola" urine suggest glomerular bleeding and a Nephrology referral is recommended in these cases.

4. Rule out urinary TB

Patients with unexplained hematuria who are from a country with a high tuberculosis incidence (see Appendix A5) should be investigated for potential urinary TB. In these patients, at least 3 early-morning (first void) urine samples should be sent for acid-fast stain.Use the CLS Microbiology Requisition to order this test, and write “Acid-fast stain” after “Other - specify:” under the Urine section. A urine mycobacterial culture should also be automatically performed on these samples.

5. Referral

If the patient’s microscopic hematuria is still unexplained after the above investigations, a referral to a Urologist for cystoscopy is then warranted.

- Refer to the Calgary Zone Urology Referral Quick Reference for the referral process of patients with hematuria in Calgary.

LEAD

POISONING

Most cases of lead poisoning happen in children living in low-income regions. Therefore, young refugee patients (particularly those under 6 years of age) are at risk of lead poisoning. While we do not recommend routine screening asymptomatic children with lead levels, screening can be considered in children age <6 who have lived in poverty or are iron deficient

(since this can increase lead absorption).

It is also essential to test all refugee children with unexplained neurocognitive deficits (developmental delay, low IQ), hearing loss or nephropathy. Any detectable blood lead level result should be discussed with a Pediatrician.

MALARIA

Malaria should be suspected in any patient from an endemic country (see

Appendix A6 for a map of malaria endemic countries) with fever

(usually cyclical but not necessarily)* or a combination of the following symptoms:

- Malaise/chills

- Myalgia/arthralgia

- Tiredness

- Nausea/vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Dry cough

- Sore throat

* Remember that not all patients with malaria present with fever. Family doctors should maintain a high index of suspicion

for malaria when refugee patients present with non-specific illness symptoms (e.g. flu-like symptoms).

Also look for signs of anemia and splenomegaly on exam, in addition to any alarming sign such as convulsion, altered consciousness, shock, jaundice, hemoglobinuria and hypoglycemia.

Patients who have recently arrived (in the last 3 months)

from an endemic country are especially at risk of symptomatic malaria, but Plasmodium vivax and ovale

infections can sometimes manifest months and even years after exposure.

TESTING

If malaria is suspected, testing should be ordered as soon as possible. If testing cannot be performed in the community on the same day or if rapid follow-up of the results is not possible (e.g. end of the day or before the weekend), the patient should be sent to the Emergency Department to be tested there. Calgary Laboratory Services have recently changed their testing algorithm. Only one test, a nucleic acid amplification test (NAT), is now performed. This is a very sensitive blood test (97-100%), and malaria smears will only be performed if the NAT is positive. To order this test, you need to order malaria testing under Blood/Sterile Fluids on the CLS Microbiology Form, and complete the CLS Malaria History Form.

These forms are available on the CLS

website.

If the patient has fever and malaria is ruled out with appropriate testing, other infectious diseases (such as dengue, chikungunya, enteric fever, influenza, hepatitis, liver abscess, brucellosis, meningitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis

and leptospirosis) should then be considered depending on the other associated symptoms (rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, cough, etc.). This is however outside the scope of the present guidelines, and an Infectious Diseases consultation

should be considered in these cases.

For an approach to fever in the returned traveler (or refugee), refer to the following guidelines:

- Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) guidelines

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines

TREATMENT

The role of the community family physician is to be alert for potential malaria symptoms and diagnose the infection quickly. Any diagnosed case of Plasmodium falciparum

infection

should be urgently

referred to the Emergency Department. This is because even uncomplicated cases of P. falciparum

can rapidly evolve in severe malaria and thus treatment should be initiated under observation as soon as possible. While uncomplicated cases of non-falciparum malaria (P. vivax, ovale, malariae, knowlesi) can be treated in the community, this requires special expertise, and a consultation with an Infectious Diseases specialist is recommended.

- Refer to the Canadian Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Malaria by the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) for more information on the diagnosis and treatment of malaria, including the criteria for severe malaria.

POST-TRAUMATIC

STRESS DISORDER

SCREENING

As mentioned in the Initial Medical History in Refugee Patients

section, we recommend against routine screening for a history of traumatic events in refugee patients. However, since a lot of refugees and refugee claimants will have experienced or witnessed traumatic events, physicians should be aware of potential post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms such as hyperarousal, intrusive thoughts avoidance, guilt, irritability,

and sleep disturbance (especially nightmares). Remember that refugee patients with underlying psychiatric disorders will often complain of somatic symptoms

first.

In patients who have experienced traumatic events, the Primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5

can be used as a screening tool:

- Had nightmares about the event(s) or thought about the event(s) when you did not want to?

- Tried hard not to think about the event(s) or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of the event(s)?

- Been constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?

- Felt numb or detached from people, activities, or your surroundings?

- Felt guilty or unable to stop blaming yourself or others for the event(s) or any problems the event(s) may have caused?

Patients who answer “yes” to 3 or more questions should definitely be assessed further for PTSD.

If the patient screens positive with the above tool, the

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) can then be used to provide a provisional PTSD diagnosis.

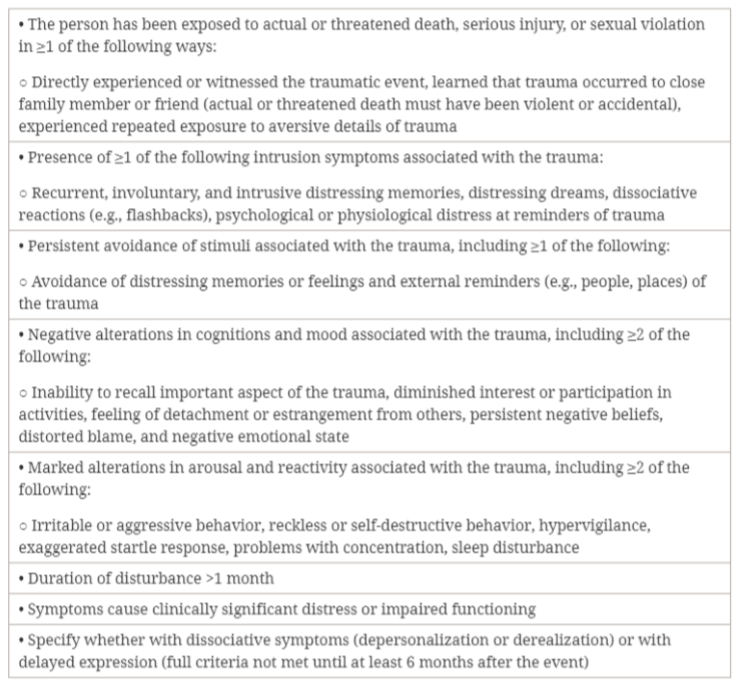

PTSD is diagnosed in patients older than 6 years old who meet all

of the following DSM-5 criteria:

Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Katzman et al., 2014).

TREATMENT

Patients with confirmed or suspected PTSD should be screened for comorbid conditions such as substance abuse, mood disorders, and

suicidality. These patients should be

referred to a Psychiatrist for diagnostic assessment and management. In Calgary, this should be done through

Access Mental Health (phone: 403-943-1500). While waiting for the referral, family physicians should initiate treatment.

Treatment for PTSD consists of 2 main components: psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy:

Psychotherapy

Trauma-focused therapy

that includes exposure should be strongly encouraged in PTSD patients. For refugee patients in Calgary, we recommend a referral to the Centre for Refugee Resilience

by the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society. Access Mental Health

is another resource that can be used to refer patients for psychotherapy.

Pharmacotherapy

- Address sleep concerns first

If the patient’s sleep is disturbed, we usually start with a trial of prazosin. It works well for PTSD-related nightmares and night-time hyperarousal (can be combined with SSRI or SNRI). We usually start with 1 mg at bedtime and increase the dose progressively. Dose titration differs between men and women: females usually require lower doses, and doses can be titrated up more rapidly in males (see The Psychopharmacology Algorithms by the Harvard Medical School below). Remember that this is an anti-hypertensive agent and thus patients should watch for symptoms of orthostatic hypotension. Prazosin should not be discontinued suddenly because of the risk of rebound hypertension. Trazodone can also be tried if sleep onset is impaired. - Consider a trial of SSRI or SNRI

If symptoms persist after addressing the sleep disturbances or if sleep is not a concern, antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs can be used to reduce PTSD symptoms. We usually start these medications at a low starting dose and titrate up the dose gradually (every 3-4 weeks) until a response is achieved. Doses for PTSD are similar to the ones used for depression. In the literature, the recommended first-line agents are: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and venlafaxine.

At the Calgary Refugee Health Program, our preferred first-line agent is sertraline because it is usually better tolerated. If sertraline is not effective or not well tolerated, we then recommend trying venlafaxine. We sometimes try venlafaxine before sertraline when the noradrenergic component is needed, rather than the sedating potential of sertraline. We usually avoid paroxetine because of its side effect profile and risk of discontinuation syndrome (which can be a significant issue in refugee patients). Second-line agents are not covered in these guidelines. We suggest not using benzodiazepines in PTSD patients.

- Refer to the Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, post-traumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders for more extensive guidelines.

- The Psychopharmacology Algorithms by the Harvard Medical School also provide a useful algorithm for the treatment of PTSD, including suggested dosing protocols for prazosin.

SCABIES

Scabies is an infestation of the skin by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei

that is especially common in resourcelimited regions and crowded conditions such as refugee camps. Therefore, newly arrived refugees are at risk. It is transmitted through prolonged skin-to-skin contact which means that family members and sexual partners are at risk. After a primary infestation, it may take up to 8 weeks before the symptoms appear.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

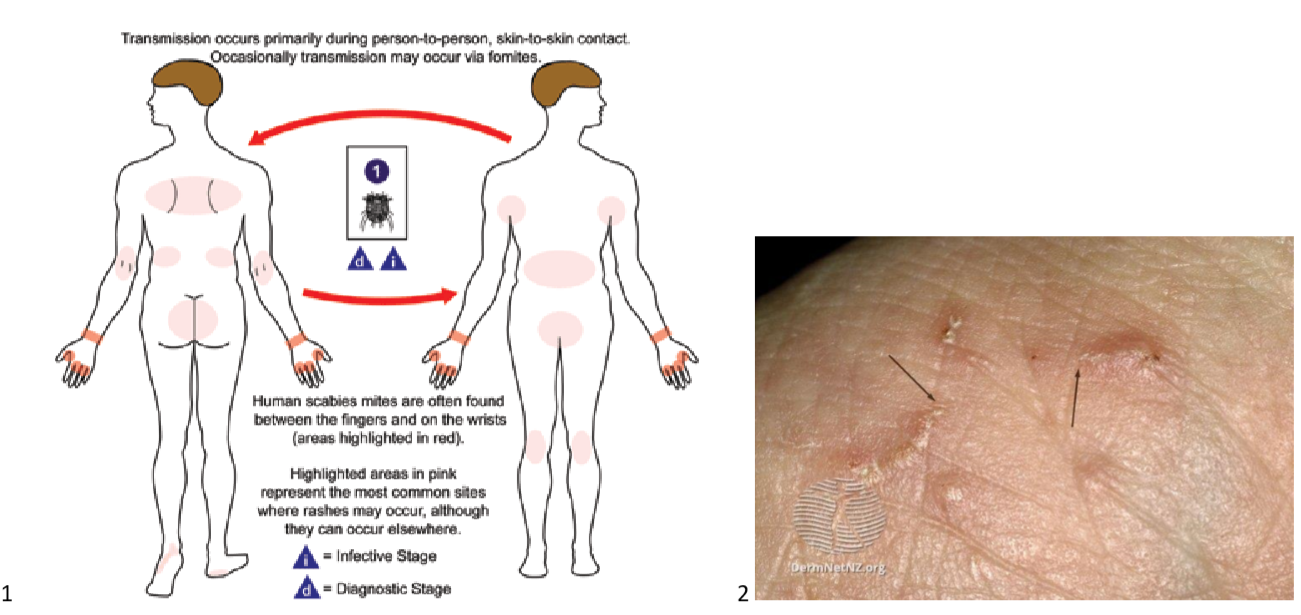

The main symptom is severe pruritus that is worse at night. On exam, multiple small erythematous papules can be found, and mite burrows (small serpiginous lines) can sometimes be seen. The head is usually spared. Here are the common locations of the scabies rash

as well as an example of the typical rash:

A definitive diagnosis is made by microscopy of skin scrapings from high-yield locations (fingers, sides of hands, flexural wrists, elbows, axillae, groin, breasts, and feet). However, considering that this test lacks sensitivity and that it might take a few days to obtain the results, treatment should be initiated in any patient with typical pruritus and skin lesions.

TREATMENT

The first-line therapy for scabies is topical permethrin

(30g per application for adults). Patients with scabies as well as any close contact (even if asymptomatic) should be treated simultaneously. Patients should be instructed to apply the cream everywhere

from the neck to the soles of the feet (including under the nails) and leave it on the skin overnight for at least 8 hours. In young children, the cream should also be applied to the scalp and the face (sparing the eyes and mouth). We recommend a second permethrin application 1-2 weeks after the first one to ensure eradication of the mites. Permethrin is safe in pregnant and lactating women and in infants ≥2 month of age.

Pruritus and active skin lesions should cease 1 week after successful treatment, but can sometimes persist for up to 1 month.

Oral ivermectin

(200 mcg/kg single dose followed by a repeat dose 1-2 two weeks later) is an alternative to permethrin that can be considered in patients who have failed treatment with permethrin or who are not compliant with the topical permethrin regimen. As for the strongyloidiasis treatment, patients from a loa loa endemic country should not take ivermectin unless loiasis has been excluded (see Positive Strongyloides Serology).

TINEA

CAPITIS

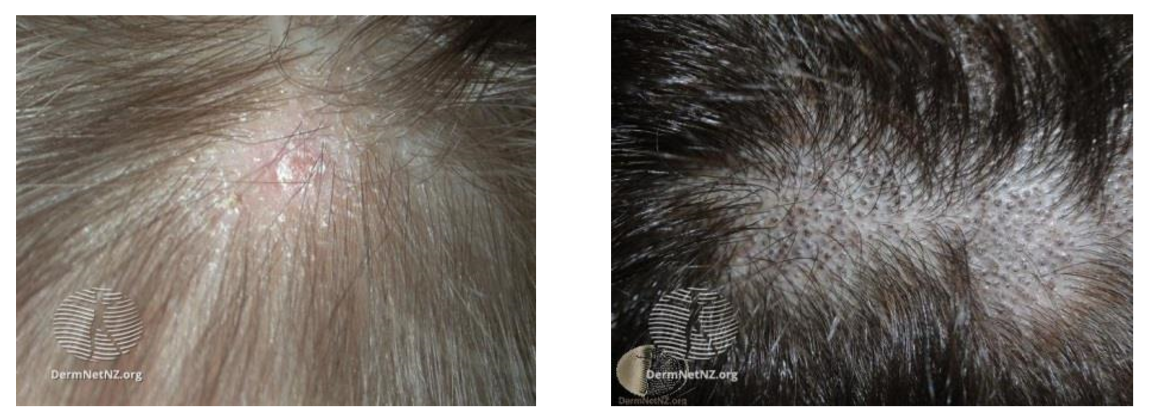

Tinea capitis is a common disorder in prepubertal refugees, especially those from the African continent. It will usually present with patches of alopecia (with scaly or black dots appearance), although widespread scaling with subtle hair loss is also possible (which can resemble seborrheic dermatitis).

DermNet NZ.

Tinea capitis.

We recommend a fungal culture to confirm the diagnosis, but if a child presents with typical tinea capitis lesions, treatment should be started right away without waiting for the culture results. Close contacts (especially children) should also be examined to look for tinea capitis lesions.

TREATMENT

The treatment of choice is

oral terbinafine for 6 weeks*. Here are the recommended doses of terbinafine

tablets based on weight:

- 10 to 20 kg**: 62.5 mg daily

- 20 to 40 kg: 125 mg daily

- >40 kg: 250 mg daily

Baseline ALT and AST should be ordered prior to initiating treatment and should be repeated with the addition of a CBC if treatment has to be extended beyond 6 weeks.

* 6 weeks for Trichophyton

infections; Microsporum infections might require a longer regimen.

** Terbinafine is technically only approved in children > 4 years old, but we have used it in younger children with no adverse effects.

Follow-up should be performed at the end of the treatment to ensure clinical clearance. Complete hair regrowth occurs in most children with hair loss after successful treatment.

VITAMIN D

DEFICIENCY

Vitamin D deficiency is very common in refugee patients (Aucoin et al., 2013). Because of this, instead of screening for vitamin D deficiency, we simply offer vitamin D supplementation to all refugees and refugee claimants. This is especially important for women of child bearing age and children. We usually prescribe supplements for 3 months and renew the prescription if the patients have been taking it.

Here are the usual initial vitamin D supplements

we prescribe to our refugee patients (all covered by the Interim Federal Health Program):

- Exclusively breastfed children and children who cannot swallow pills

Ddrops (preferred) or D-Vi-Sol drops 800 UI once daily

- Children who can swallow pills

Vitamin D3 1000 UI tablet once daily

- Adults

Vitamin D2 50,000 UI tablet once weekly*

* If the patient wants a long-term renewal after 3 months, we then usually offer a 50,000 UI monthly prescription.