COMMON FINDINGS ON SCREENING TESTS AND SUGGESTED MANAGEMENT

COMPLETE

BLOOD COUNT

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Iron deficiency anemia (and iron deficiency without anemia) is very common in refugees, especially in women and young children. Although an iron deficient diet is a common cause of anemia in refugee patients, potential blood loss (mainly abnormal uterine and gastrointestinal bleeding) should always be considered in these patients as for the rest of the population.

- Refer to the 2018 Alberta Toward Optimized Practice (TOP) guidelines for a recommended diagnostic approach to iron deficiency anemia in the general population.

UNDERLYING ETIOLOGY

Always wait for the complete hemoglobinopathy screen results before interpreting the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) since patients with some traits such as alpha-thalassemia can have lower MCV even in the absence of iron deficiency.

In refugee patients,

H. pylori

infection and

parasitic infections (mainly hookworms and whipworms) are common causes of iron deficiency and should be considered in any anemic patient, especially if gastrointestinal symptoms are present (see the page

Other Commonly Encountered Medical Conditions in Refugee Patients). Parasites are especially common in refugee children. Although it is more common in patients of European ancestry, celiac disease

should be considered as a cause of iron deficiency in refugee patients. Hematuria

should also be ruled out in cases of unexplained iron deficiency anemia.

In asymptomatic adult refugee

patients who fit the criteria for assessmentof

potential occult GI bleeding (see TOP guidelines), but who are at low risk of GI malignancy (<50 years old, no family history),

it is reasonable to begin with the following investigations before referring them for GI endoscopy:

- H. pylori stool antigen test

- Stool Ova & Parasites examination (preferably 3)*

- Celiac Screen

- Urinalysis

* Based on our experience with our refugee patients, it is often difficult to obtain a proper stool sample to perform this test. In these cases, it is reasonable and safe to simply treat empirically for helminth infections with mebendazole (500 mg once or 100 mg twice daily for 3 days - for patients ≥ 2 years of age.

TREATMENT

If iron deficiency is diagnosed, the underlying cause should be addressed and all patients should be offered treatment with iron supplements. Ferrous sulfate

(both the tablets and the oral solution for children) is the only iron formulation that is covered by the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP).

Iron supplements should be taken with orange juice to increase absorption. A repeat CBC and iron studies should be repeated after 3 months of supplements. For patients with symptoms of anemia or significant anemia (<90 g/L), refer to the TOP guidelines for treatment recommendations.

In addition to prescribing iron supplements, we counsel all our iron deficient refugee patients on

iron-rich foods.

Here are the regimens we usually recommend for our asymptomatic refugee patients with iron deficiency:

- Adults

Ferrous sulfate tablets 300mg tablets (60 mg elemental iron) twice a day for 3 months

- Children

Ferrous sulfate drops (15 mg/mL elemental iron) 6 mg/kg/day divided once or twice a day for 3 months.

Neutropenia

Neutropenia is common in refugees and is mainly due to benign ethnic neutropenia (BEN)

in patients of African and Middle Eastern descent. The diagnosis of BEN is based on persistent mild

neutropenia in a patient with an appropriate ethnic background

and without a history of recurrent infections. This is a benign condition with no increased incidence or severity of infection.

Patients from other ethnic descents with neutropenia should be investigated for other etiologies. Potential systemic symptoms (e.g. fever), medications that can cause neutropenia and signs of infection, malignancy and liver disease should all be assessed.

Our recommended approach for asymptomatic patients with neutropenia based on their absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in 10E9/L*:

- 1.5

No follow up is required. - 1.0 to 1.5 (mild)

We recommend repeating at least one CBC (with an interval of at least 2 weeks between the tests). If the neutropenia is still mild and not clearly trending down, and the patient is of African or Middle Eastern descent, we usually consider BEN as the cause of the neutropenia. Since this is a genetic condition, BEN is even more likely if other family members are also neutropenic. - 0.5 - 1.0 (moderate)

Although the ANC in BEN can occasionally be <1.0 (especially in women), this is not a common finding (usually >1.2). In these cases, a repeat CBC as well as a blood smear should be ordered, and potential etiologies should be sought on history and exam. Again, neutropenia in other family members could suggest BEN as the cause of the neutropenia. - <0.5 (severe)

These patients should be evaluated immediately if symptomatic, preferably in a hospital setting. If they are asymptomatic, it is reasonable to call a Hematologist before referring the patient to the hospital.

* Keep in mind that the values above apply mainly to adult patients. Children will have different normal neutrophil count values depending on their age.

Eosinophilia

The differential diagnosis of eosinophilia is vast, but helminth infections are a very common cause of eosinophilia in refugee patients and should be ruled out first before investigating other etiologies (unless the clinical presentation suggests another cause).

Our step-wise approach for refugee patients with eosinophilia:

- Rule out strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis

Strongyloides and schistosoma serologies should have already been ordered as part of the initial screening tests. Treat if positive (see Positive Strongyloides Serology and Positive Schistosoma Serology sections), and follow-up with a repeat CBC at least 4 weeks later to reassess the eosinophil count. If the eosinophilia is still present, another cause should then be considered. - Look for Helminth infections

Order at least 3 serial stool Ova & Parasites examinations* to look for other potential helminth infections (mainly hookworms and flukes). Stool microscopy is not a sensitive test and repeat testing is thus recommended to increase the sensitivity.

However, based on our experience with our refugee patients, it is often difficult to obtain a proper stool sample to perform this test. In these cases, it is reasonable and safe to simply treat empirically for helminth infections with mebendazole (500 mg once or 100 mg twice daily for 3 days - for patients > 2 years of age). See Other Medical Conditions Encountered in Refugee Patients for the treatment of common gastrointestinal parasites. - Test for other parasites

If the initial serologies and stool examinations did not reveal any helminth infection, then other parasitic causes such as trichinella, filariae, flukes and toxocara (mainly in children) should be ruled out. These investigations should however be ordered by an Infectious Diseases specialist**. - Look for other causes

The non-infectious causes of eosinophilia should also be considered (especially if the parasitic work-up is negative): medication-related eosinophilia, asthma/atopic disease, hematologic diseases, vasculitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome), diseases with specific organ involvement (skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart…), etc. The following basic investigations can be ordered as a first step: peripheral blood smear, electrolytes, creatinine, urinalysis, B12 levels, liver function tests, troponin, and chest X-ray.

The complete work-up for these potential causes is however outside the scope of this resource.

* Do not forget to fill out the CLS Stool & Parasite History Form

when ordering these tests.

** In Calgary, the Tropical Infectious Diseases Clinics Calgary

is a good place to refer these patients.

POSITIVE

HEMOGLOBINOPATHY SCREEN

Thalassemia variant alleles are common in patients from Africa, Mediterranean countries and parts of the Asian continent. Sickle cell trait is distributed throughout the world with high prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa, some Mediterranean countries and the Middle East.

Alpha-thalassemia

Alpha-thalassemias are caused by gene deletions (sometimes mutations) on one of the 4 alpha globin genes:

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Thalassemias.

We often find the

silent carrier status (1 missing gene) and alpha-thalassemia trait

(2 missing genes) in refugee patients. Silent carriers are asymptomatic and have normal red blood cells. Patients with the alpha-thalassemia trait will only have mild anemia with hypochromia and microcytosis.

Patients who are missing 3 genes have hemoglobin H disease. These patients should be referred to a Hematologist. The clinical severity is variable. Most patients are not transfusion-dependent but might require episodic transfusions (during pregnancy for example). They should take folic acid supplements (1-2mg daily) and avoid iron supplements unless they are clearly iron deficient.

If a patient has any of the alpha-thalassemia alleles mentioned above and is planning a pregnancy, his/her partner should also be tested. Based on the parents’ alleles, if there any risk of hemoglobin H disease or hydrops fetalis (4 missing genes) in the fetus, they should be referred to Medical Genetics for pre-conception counselling.

Beta-thalassemia

Beta-thalassemias are caused by mutations on one of the 2 beta globin genes:

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).Thalassemias.

The mutations can cause either reduced expression (β+) or absence of expression (β0), which will influence the severity of the disease.

Beta-thalassemia major patients (β0/β0 or β0/β+) will have severe life-long transfusion-dependent anemia. Unless they are very young, refugee patients with this condition will usually have already been diagnosed in their country of origin.

Beta-thalassemia intermedia patients (β+/β+) will usually have moderate microcytic anemia and may require transfusion later in life. Both major and intermedia patients should be referred to a Hematologist. The management of these conditions is outside the scope of these guidelines.

Beta-thalassemia minor (β/β0 or β/β+) are usually asymptomatic and may have mild anemia in addition to marked microcytosis.

If a patient has any of the beta-thalassemia alleles mentioned above and is planning a pregnancy, his/her partner should also be tested. Based on the parents’ alleles, if there is any risk of beta-thalassemia major or intermedia in the fetus, they should be referred to Medical Genetics for pre-conception counselling.

Sickle Cell Disease

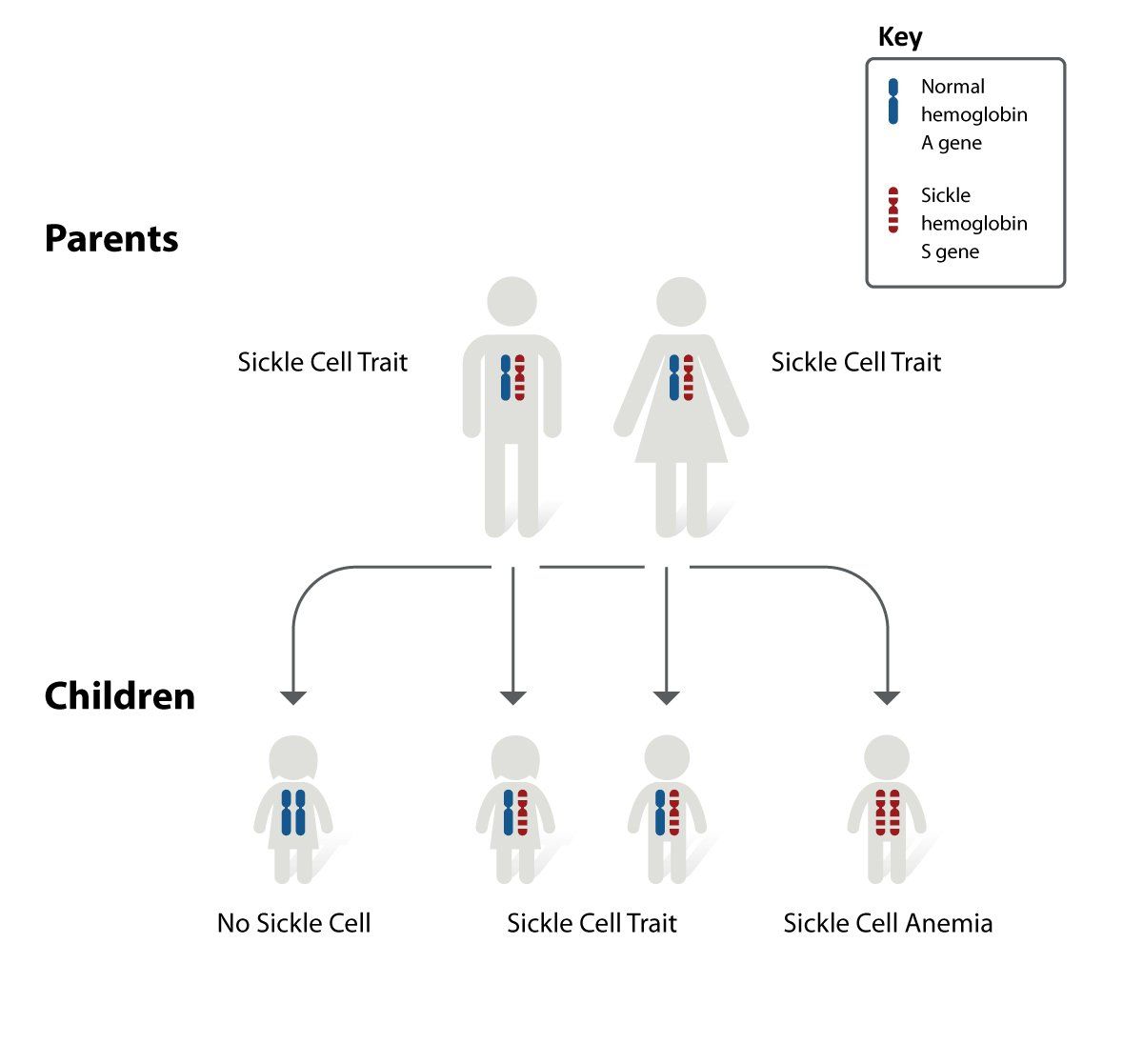

Sickle cell trait and disease (allele S) are due to a mutation in the beta globin gene (normal - allele A):

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Sickle Cell Disease.

Although patients with sickle cell trait

(HbAS) may be at higher risk of certain conditions such as a higher prevalence of renal disease and thromboembolic events, they are usually asymptomatic and should be managed as the rest of the general population.

Sickle cell disease patients (HbSS) have chronic hemolytic anemia and are at high risk of multiple conditions: vaso-occlusive episodes, acute chest syndrome, severe infection, aplastic crisis, stroke and TIA, renal insufficiency, avascular necrosis, retinopathy,

and many others.

While all sickle cell disease

patients should be followed by a Hematologist, the family physician can still play a role in the education and preventive care of these patients. Here are a few elements that can be addressed by the family physician, especially while waiting for the initial hematology consult:

- Education about potential dangerous symptoms

Patients/families should seek prompt medical attention whenever a patient with sickle cell disease has fever, acute bodily pain, abdominal pain, chest pain, respiratory symptoms, neurological symptoms or priapism. Families should have a thermometer at home to monitor for fever. Until patients/families are comfortable with the management of vaso-occlusive painful episodes, any bodily pain should be assessed by a physician who has experience treating complications of sickle cell disease. - Education about the triggers of vaso-occulsive episodes

Dehydration, illness, fever, surgery, exposure to cold and psychological stress. - Infection prophylaxis

Sickle cell patients should receive antimicrobial prophylaxis from age 2 months to 5 years. Patients under 3 years old should take Penicillin V 125mg twice daily and patients over 3 years old should take Penicillin V 250mg twice daily. - Vaccination

All sickle cell patients should be referred for pneumococcal (PCV13 and PPV23) and meningococcal (serogroups B + ACYW-135) immunization, as well as the routine immunization schedule. - Nutrition

Growth should be monitored at every visit. All sickle cell patients should take a daily folic acid supplement (1mg). Also, they should be offered a daily multivitamin without iron. Because of the risk of iron overload, iron-containing supplements should be avoided unless the patient is shown to be iron deficient. Review the patient’s intake of calcium and vitamin D and recommend supplements if needed. - Renal function monitoring

Blood pressure measurement as well as serum creatinine, urine microscopy and urine microalbumin should be done annually. - Referral for screening ophthalmologic examination

Because of the risk of retinopathy, all newly diagnosed sickle cell disease patients should be referred for a full ophthalmologic examination. If the initial exam is normal, the patient should have a routine follow-up every 1-2 years.

Variant combination sickle cell syndromes, such as

Hemoglobin SC disease and

Sickle beta thalassemia, are also sometimes diagnosed in refugee patients, but these are not covered in this resource.

Refer to the

CanHaem Consensus Statement on the Care of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in Canada for more information.

G6PD

DEFICIENCY

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency is an X-linked inherited disorder caused by a genetic defect in the red blood cell enzyme G6PD, which serves to protect red blood cells from oxidative injury. It can cause jaundice in newborns as well as acute hemolytic anemia in patients exposed to oxidant stress exposures (see below).

Since it is an X-linked disorder, males are usually affected. This is why we recommend screening males only. Heterozygous female patients can have lower levels of G6PD but these are rarely clinically significant. However, all patients (men and

women) with Plasmodium vivax

or ovale

malaria infections should be screened for G6PD deficiency before receiving primaquine (used to eradicate the dormant liver stages of these parasites).

DIAGNOSIS

A screening test is usually performed first, followed by a quantitative confirmatory test if a deficiency is detected. In Calgary, the screening test should be ordered by writing "G6PD" in the "Other tests not listed" on the Calgary Laboratory Services Community General Requisition. If indicated, the quantitative test is then usually done automatically by the laboratory.

As per the World Health Organization, clinically significant G6PD deficiency

is classified as enzyme activity <30% (<3 U/g Hb) in adults and children >12 months of age. Although some patients might have a mild deficiency (3-8 U/g Hb), they are usually less at risk of oxidative stress. These patients should still be counselled about potential oxidative stressors.

PATIENT EDUCATION

The diagnosis should be carefully explained to the patients. They should be told about the foods and drugs that can precipitate acute hemolysis (especially the most common ones). A list is available in

Appendix A3, as well as an information card that patients with clinically significant G6PD deficiency should carry in their wallet to show to healthcare practitioners at their medical appointments. We usually show them pictures of fava beans, mothballs and henna to make sure they avoid these substances.

Patient should also be made aware of the symptoms of acute hemolysis and immediately seek medical help if they have any of them (mainly jaundice, pallor and dark urine).

HEPATITIS B

SEROLOGIC TESTS

For the interpretation of hepatitis B serologic test results, refer to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

website.

Susceptible (Not Immune)

Patients with anti-HBs levels < 10 IU/L are considered not protected against hepatitis B and should be offered immunization. We offer hepatitis B vaccination in susceptible refugees because these patients are likely to go back to their country of origin in the future to visit family and friends and will then be exposed to the virus.

In Alberta, children should be vaccinated in school. Adults from

high endemic countries (see

Appendix A9 for the list of countries)

or who

were born in 1981 or after, are also eligible for hepatitis B immunization through Alberta Health Services (AHS). They should be referred to any AHS Community Health Centre to be vaccinated.

For adult refugees who do not fulfill the criteria mentioned but still want to be immunized against hepatitis B, the vaccine is actually covered by the IFHP (both hepatitis B alone and hepatitis A&B combination) and can be prescribed by a physician to be picked up at a pharmacy.

Immune due to Previous Infection or Vaccination

For patients with anti-HBs levels >10 IU/L, due either to a previous cleared infection (anti-HBc pos) or vaccination (anti-HBc neg), no further management is recommended.

Unclear(HBsAg neg, anti-HBc pos, anti-HBs <10IU/L)

In cases of isolated anti-HBc positivity, there are 4 diagnostic possibilities:

- Resolved infection (with waning anti-HBs levels many years after recovery)

Since a remote resolved infection is the most common cause of isolated anti-HBc positivity, we usually do not order any further testing. Even with negative anti-HBs levels in these cases, we do not recommend hepatitis B immunization in refugee patients because they have likely already been exposed to the virus and will not respond to vaccination. - False-positive anti-HBc (susceptible)

This happens mainly in low-risk patients, which is rarely the case with refugee patients. - Occult hepatitis B infection with undetectable HBsAg

Since occult infections are quite rare, we do not recommend routinely ordering HBV DNA levels to rule it out. However, since these occult infections can still lead to liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma, they should be ruled out in patients who have concomitant HIV or hepatitis C infections, develop signs or symptoms suggestive of liver disease (e.g. elevated AST/ALT levels) or might be immunosuppressed in the future. - Resolving acute infection

This should be suspected if the patient had recent symptoms suggestive of acute hepatitis. Anti-HBc IgM levels can help rule out a recent infection and are usually performed automatically by the lab in these cases.

Acute or Chronic Infection

(HBsAg positive)

If the patient presents signs of acute

hepatitis B infection (HBsAg pos, IgM anti-HBc, elevated ALT, symptoms - mainly in adults), a consultation with a Hepatologist is recommended.

The diagnosis of chronic

hepatitis B is based on the persistence of HBsAg for more than 6 months. However, refugee patients who are HBsAg positive and have no signs of acute hepatitis should be managed as probable

chronic hepatitis B patients from the beginning without having to wait for the confirmation 6 months later.

Patients with chronic hepatitis B

can be initially managed by their family physician while waiting for the Hepatologist consultation. Here are the initial steps that should be followed:

- Report the infection to the appropriate public health agency

Hepatitis B is a notifiable disease in Alberta. The lab will usually automatically notify the AHS Communicable Disease Unit. They should then contact the ordering physician to request additional information (symptoms, contacts, pregnancy status, etc.). An adequate public health investigation will be performed to notify and offer testing to potential contacts. If the ordering physician has not been contacted by the Communicable Disease Unit, he/she should contact them to make sure they have been notified of the case (Phone: 403-955-6750, Fax: 403-955-6755). - Appropriate post-diagnosis counselling

Disclose the diagnosis to the patient in a culturally-sensitive manner, using an interpreter if required. Explain the various modes of hepatitis B transmission (and how to avoid transmitting the virus - condoms, no sharing of razors, no blood donation, etc.). They should understand the potential consequences of the infection (hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis) as well as the concept of chronic infection.

They should know that there is no cure at the moment and that while some people can clear the infection by themselves, most patients will be chronically infected (for decades or life). Explain that treatment is only offered in certain hepatitis B patients at risk of disease progression, and that additional investigations are required to decide if they require treatment at this time. - Complete the history

Inquire about any potential history of symptomatic hepatitis in the past. Ask about any family history of hepatitis B, hepatocellular carcinoma or any other liver disease. Alcohol intake as well as sexual history should be addressed. Ask about any potential symptom of cirrhosis on history (jaundice, abdominal distension, history of upper GI bleeding, constitutional symptoms - anorexia, weight loss, fatigue). - Complete the physical exam

Look for any potential sign of liver disease/cirrhosis - jaundice, spider angiomata, gynecomastia, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, caput medusae, palmar erythema, asterixis, etc. - Screen contacts

Close family members as well as sexual contacts should be screened for hepatitis B and offered vaccination if susceptible (immunization should be covered for these patients). This should be organized by the Communicable Disease Control department. - Vaccination

Once the hepatitis A serology has been ordered, chronic hepatitis B patients should be referred for specific immunizations - pneumococcal and hepatitis A (if non-immune). - Order the initial blood tests

The following initial tests should be ordered after a chronic hepatitis B diagnosis: - Quantitative HBV DNA*, CBC, INR, Creatinine, ALT, AST, Ferritin, Albumin, Bilirubin total, GGT, Protein, IgG-IgA-IgM, ANA, Anti-Hep A IgG, HBeAg, Anti-HBe, HIV and HCV serologies, Alpha-1 antitrypsin, Anti-SMA, AMA

- Begin hepatocellular carcinoma screening

Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with an abdominal ultrasound** q6 months should be initiated if the chronic hepatitis B patient fulfills one the following criteria: - Any patients with cirrhosis

- Any patient with HIV or HCV co-infection

- People of African descent 20 years of age or older

- Men 40 years of age or older

- Women 50 years of age or older

- Any patient with a family history of HCC

- Hepatology referral

All chronic hepatitis B patients should be seen by a Hepatologist at some point. However, unless there are potential indications for treatment (elevated HBV DNA or ALT, HIV/HCV co-infection, cirrhosis), patients do not have to be seen right away by the specialist and the wait time might be a few months. Pregnant patients with hepatitis B are an exception and should be seen as soon as possible by a specialist. In Calgary, patients have to be referred to a Hepatologist through the Calgary Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology Central Access & Triage (Fax: 403-944-6540). - Follow-up blood tests

Unless advised otherwise by the specialist, chronic hepatitis B patients should have follow-up blood tests done every 6 months to make sure there are no signs of disease progression. At the Calgary Refugee Health Program, we usually do the following tests: - CBC and ALT q6 months

- Quantitative HBV DNA q12 months (with "Treatment monitoring" as the "Reason for testing")

Refer to the guidelines from the Public Health Agency of Canada for more information on the management of hepatitis B.

Refer to the

guidelines from the Public Health Agency of Canada for more information on the management of hepatitis B.

* To order an HBV DNA test in Alberta, use the ProvLab Serology and Molecular Testing Requisition form, and indicate "Assessment of viremia (HBsAg+)" as the "Reason for Testing"

** For HCC screening in Calgary, we usually refer our patients to the EFW Radiology Screening Program using their Liver Program requisition form.

HEPATITIS C

SEROLOGY

Indeterminate Hepatitis C Serology

An HCV RNA test* should be ordered for all patients with an indeterminate serology in order to rule out hepatitis C infection.

* To order an HCV RNA test in Alberta, use the

ProvLab Serology and Molecular Testing Requisition form, and indicate "Assessment of viremia" as the "Reason for testing".

Positive Hepatitis C Serology

Patients with a positive hepatitis C serology

should be tested for HCV RNA

(see link to requisition above) to confirm active infection. With this blood test, we also usually order these other baseline investigations:

CBC, INR, Creatinine, ALT, AST, Ferritin, Albumin, Bilirubin total, GGT, Protein, IgG-IgA-IgM, ANA, Anti-Hep A IgG, HBsAg, anti-HBs, anti-HBc, HIV serology, Alpha-1 antitrypsin, Anti-SMA, AMA

If the patient has a positive viral load, HCV genotyping

is then required in preparation for treatment. In Alberta, all first time HCV PCR positive specimens with viral loads >500 copies/ml will automatically undergo HCV genotype determination.

Chronic hepatitis C

is defined by the persistence of HCV RNA

in the blood for >6 months. However, as for hepatitis B, patients with one positive HCV RNA result should still be managed as probable chronic hepatitis C patients from the beginning.

The new direct-acting antiviral (DAA)

regimens, with cure rates close to 100%, have drastically changed the treatment of hepatitis C patients. This is why hepatitis C patients should be referred to a Hepatologist (see below) as soon as possible.

Once a current hepatitis C infection (HCV RNA+)

is confirmed, the following steps should be followed by the patient’s family physician while waiting for the Hepatologist consultation:

- Report the infection to the appropriate public health agency

Hepatitis C is a notifiable disease in Alberta and should be reported to the AHS Communicable Disease Unit. The lab usually notifies the Communicable Disease Unit who then contacts the patient, but it is reasonable to contact them to make sure they are aware of the case (Phone: 403-955-6750, Fax: 403-955-6755). An adequate public health investigation should then be performed to notify and offer testing to potential contacts. - Appropriate post-diagnosis counselling

Disclose the diagnosis to the patient in a culturally-sensitive manner, using an interpreter if required. Explain the various modes of hepatitis C transmission (and how to avoid transmitting the virus - no needle sharing, condoms, no blood donation, etc.). They should understand the potential consequences of the infection (hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis) as well as the concept of chronic infection. Explain that there is a cure for hepatitis C and that this will be prescribed by a specialist. The importance of adhering to the full treatment regimen (usually 3 months) should be stated. - Complete the history

Inquire about any potential history of symptomatic hepatitis in the past. Ask about any family history of hepatitis C, hepatocellular carcinoma or any other liver disease. Injection drug use is the most common cause of hepatitis C transmission, and thus patients should be asked about this. In addition, alcohol intake as well as sexual history should be addressed. Contrarily to the regular Canadian population, blood transfusions and nosocomial transmission (contaminated needles) are common modes of hepatitis C transmission in the refugee population and refugee patients should be questioned about this. Ask about any potential symptom of cirrhosis on history (jaundice, abdominal distension, history of upper GI bleeding, constitutional symptoms - anorexia, weight loss, fatigue). - Complete the physical exam

Look for any potential sign of liver disease/cirrhosis - jaundice, spider angiomata, gynecomastia, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, caput medusae, palmar erythema, asterixis, etc. - Screen contacts

Sexual contacts as well as children (if the patient is a woman) should be screened for hepatitis C. - Vaccination

Once the hepatitis A and B serologies have been ordered, chronic hepatitis C patients should be referred for specific immunizations - pneumococcal and hepatitis A/B (if non-immune).

- Order the initial abdominal ultrasound

An initial abdominal ultrasound is recommended to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma and look for signs of cirrhosis. - Hepatology referral

All chronic hepatitis C patients should be seen by a Hepatologist to plan for treatment with DAAs*. At the Calgary Refugee Health Program, we usually refer our new hepatitis C patients directly to the Hepatitis C Clinic at the Calgary Urban Project Society (CUPS) (referral letter addressed to the Hepatitis C Clinic, Fax: 403-221-8785). In Calgary, patients can also be referred to a Hepatologist through the Calgary Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology Central Access & Triage (Fax: 403-944-6540).

* Although they are very expensive, DAAs have been covered for our refugee and refugee claimant patients in the past (this is usually taken care of by the Hepatologist). Coverage may however vary depending on the province. The Hepatologist might send instructions to the family doctor regarding follow-up during and after treatment. All patients will require a qualitative HCV RNA test 12 weeks after the end of treatment to ensure a sustained virologic response (i.e. cure).

Refer to the guidelines from the

Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver (Shah et al., 2018) for more information on the management of hepatitis C.

POSITIVE HIV

SEROLOGY

Steps to follow after a new HIV diagnosis:

- Post-diagnosis counselling

Once the diagnosis of HIV is confirmed, post-diagnosis counselling should be done with the patient in a confidential and culturally-sensitive manner. An HIV diagnosis should only be announced with the patient alone in the room. Remember that patients with HIV can be extremely stigmatized in some cultures. This is why we always emphasize confidentiality first. The first step is to explain the diagnosis and make sure the patient understands the transmission modes and potential complications of HIV. The patient should know that while there is currently no cure for HIV, safe and effective antiretroviral treatments are available in Canada, and these will allow him/her to live a normal life if they are taken every day. Because appearances can be very important in some cultures, we usually tell our patients that no one will be able to tell they have HIV if they stay healthy and take their medications as prescribed. - Assess for opportunistic infections

The next step is to make sure that the patient does not have any symptom or sign of an opportunistic infection - fever, cough, shortness of breath, profuse diarrhea, dysphagia, headaches, etc. If this is the case, the patient should be referred to the Emergency Department for further investigations and should not wait to be seen as an outpatient. - Report the infection to the appropriate public health agency

HIV is a notifiable disease in Alberta and should be reported to the AHS Communicable Disease Unit. The lab usually notifies the Communicable Disease Unit who then contacts the patient, but it is reasonable to contact them to make sure they are aware of the case (Phone: 403-955-6750, Fax: 403-955-6755). An adequate public health investigation should then be performed to notify and offer testing to potential contacts. The patient should be encouraged to disclose the infection to his/her close sexual partner, and children of infected women should all be tested. - Referral

All patients living in southern Alberta should be referred to the Southern Alberta HIV Program (SAC) at Sheldon M. Chumir Health Centre. Simply fax a referral letter to 403-955-6355, and the patient should be seen within 1 month at the clinic. We do not usually order any additional investigations while waiting for the referral. At the SAC, the staff will take care of ordering additional investigations (including CD4 count and viral load), initiating treatment and distributing the medications, providing the necessary vaccinations and screening for latent tuberculosis.

The treatment of HIV is outside the scope of this clinical resource and antiretroviral therapy should only be prescribed by an HIV specialist. However, family physicians following patients with HIV should be aware of the main antiretroviral drugs used in Canada as well as their most common side effects. Family physicians can also play a role in monitoring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in these patients.

Refer to the

Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE) website for a list of resources for the management of HIV.

VARICELLA

NON-IMMUNE

Patients with a negative varicella serology

should be offered immunization against varicella. For school-age children, this will be done through school in most Canadian provinces. Other patients should be referred to a local vaccination clinic.

For patients with an indeterminate varicella serology, we also offer immunization without repeating the serology. However, if the physician is planning on ordering any other blood work, it is reasonable to add a repeat varicella serology to these other tests before offering vaccination.

POSITIVE STRONGYLOIDES

SEROLOGY

Strongyloidiasis is a gastrointestinal helminthic infection that occurs in most tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Most patients will be asymptomatic but some can experience vague gastrointestinal symptoms (usually upper GI symptoms) or cutaneous manifestations such as urticarial or pruritus. However, in patients who become immunosuppressed, a potentially deadly hyperinfection syndrome can happen where the strongyloides larvae disseminate throughout the host’s body. This can happen even with a very short immunosuppression period such as a course of corticosteroids for 1 or 2 weeks. Strongyloidiasis can last for multiple decades in a single host because of the parasite’s special autoinfection life cycle. This is why it is very important to screen refugee patients and treat them adequately.

TREATMENT

In patients with a positive strongyloides serology, the treatment of choice is ivermectin:

Ivermectin 200 mcg/kg/dose2 single doses given on 2 consecutive days

While ivermectin used to be only available through the federal Special Access Programme, it has recently been approved by Health Canada and is covered by the Interim Federal Health Program since November 2018. Since it is still not available in most regular pharmacies in Calgary, we usually send the prescription to

Lukes Drug Mart in Bridgeland for delivery.

Albendazole (400 mg twice daily x 7 days) is an alternative treatment for strongyloidiasis, but it is currently only accessible through the Special Access Programme in Canada.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO IVERMECTIN

Ivermectin is very safe and usually well tolerated, but there is

one major contraindication:

a concomitant loa loa infection. Loiasis (also known as the “eye worm”) is a filarial helminthic infection that is endemic in many central African countries. While the infection in itself usually does not cause severe complications, if a patient with loiasis is treated with ivermectin, it can cause a significant inflammatory reaction leading to encephalitis. This is why any strongyloidiasis patient from a loa loa endemic country should be tested for loiasis before being treated with ivermectin (see

Appendix A10 for the geographical distribution of loa loa). Since testing for loiasis requires a special blood smear done at a specific time of the day, this should be done by an Infectious Diseases specialist*.

In addition, ivermectin should not be used during pregnancy and in children <15 kg

since safety has not been well established in these cases (The Medical Letter, 2013).

* In Calgary, the Tropical Infectious Diseases Clinics

is a good place to refer these patients.

TEST-OF-CURE

Since anti-strongyloides antibodies titers usually fall a few months after treatment, it is possible to repeat the serology 6 months post-treatment to monitor the adequacy of treatment. However, we rarely do a repeat serology at our clinic because of the high cure rates of ivermectin in immunocompetent patients. We do however recommend a test-of-cure for patients who are or will be immunosuppressed.

EQUIVOCAL SEROLOGY

In patients with an equivocal strongyloides serology, a repeat serology can be ordered. On the second serology, a positive or a second equivocal result warrants treatment. However, considering the simplicity of the treatment, in patients with an equivocal serology who are not from a loa loa endemic region, it is reasonable to offer ivermectin right away without repeating the serology.

Refer to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website for more information on strongyloidiasis.

POSITIVE SCHISTOSOMA

SEROLOGY

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic blood fluke infection that can cause severe complications in longstanding chronic infections. It is especially prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa (see

Appendix A4 for the distribution of schistosomiasis). Most African refugee patients will know this infection as “bilharzia”. The adult worms can live for years in the blood vessels surrounding the patient’s organs (mainly the bowel, liver and bladder) and will produce eggs that cause inflammation as they migrate through the tissues. This inflammation can lead to complications such as bowel ulceration and blood loss, portal hypertension, hematuria and bladder cancer.

In patients with a positive schistosoma serology, we usually inquire about potential associated symptoms such as macroscopic hematuria, dysuria, abdominal pain, diarrhea and rectorrhagia. We also look for signs of portal hypertension. We only order abdominal imaging in patients with symptoms or signs of potential liver involvement. We currently do not recommend performing a urinalysis to look for microscopic hematuria in schistosomiasis patients, since it can lead to additional unnecessary investigations. A urinalysis is not an appropriate test-of-cure for schistosomiasis. Patients with macroscopic hematuria should however be investigated accordingly.

TREATMENT

In patients with a positive schistosoma serology, the treatment of choice is praziquantel:

Praziquantel 40 mg/kg* taken in one day

divided in 2 doses (AM-PM) for better tolerance

* Because S. japonicum

and S. mekongi

infections require a higher dose of praziquantel, patients from Southeast Asia

should be treated with a dose of 60 mg/kg divided in 3 doses.

Side effects are usually mild and can include dizziness, headache, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and pruritus. Praziquantel is approved by Health Canada and is covered by the Interim Federal Health Program. Since it is still not available in most regular pharmacies in Calgary, we usually send the prescription to

Lukes Drug Mart

in Bridgeland for delivery.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO PRAZIQUANTEL

Before being prescribed praziquantel, patients should be asked about any focal neurological symptom or a history of seizure. If this is the case, praziquantel should NOT

be given to these patients since it could provoke an inflammatory response in cases of undiagnosed neuroschistosomiasis or cysticercosis. The patient should be referred to an Infectious Diseases specialist for further investigations*.

Praziquantel is safe (and recommended) to use in pregnancy

to treat schistosomiasis (Friedman et al., 2018). Since the effects of praziquantel during the first trimester have not been well assessed yet, it is preferable to wait until the second trimester to offer treatment.

* In Calgary, the

Tropical Infectious Diseases Clinics is a good place to refer these patients.

TEST-OF-CURE

Unlike strongyloidiasis, a repeat serology should not

be used as a test-of-cure. This is because anti-schistosoma antibodies titers can stay elevated for years after treatment. There is currently no test-of-cure available in Canada. However, if a patient with schistosomiasis also has eosinophilia, a repeat CBC can be an adequate follow-up test post-treatment (at least 4 weeks later).

EQUIVOCAL SEROLOGY

In patients with an equivocal schistosoma serology, a repeat serology can be ordered. On the second serology, a positive or a second equivocal result warrants treatment. However, as for strongyloidiasis, considering the simplicity and safety of the treatment, it is reasonable to offer praziquantel right away without repeating the serology.

Refer to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website for more information on schistosomiasis.

POSITIVE LATENT TUBERCULOSIS

SCREENING TEST

or Interferon-Gamma Release Assay

Both tuberculin skin tests

(TSTs) and interferon-gamma release assays

(IGRAs) are acceptable screening methods for latent tuberculosis in refugee patients. The main disadvantage of TSTs is the poor rate of return for TST reading in some patients. This is not an issue with IGRA testing, since it only requires a one-time screening blood test. However, IGRAs require fresh blood samples and special laboratory installations, and are thus not readily available everywhere in Canada.

EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH A POSITIVE LATENT TB SCREENING TEST

If a patient has a positive TST or IGRA, order a chest X-ray

to look for signs of tuberculosis:

- Apicoposterior consolidation with or without cavitation

- Mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy

- Nodular changes

- Pleural effusion

The patient should also be assessed for any potential symptoms of active TB:

- Cough for > 3 weeks

- Fever

- Night sweats

- Weight loss

- Hemoptysis

If the patient has an abnormal chest X-ray or any of the above symptoms, Calgary TB Services should be contacted immediately (Phone: 403-955-6355).

LATENT TB DIAGNOSIS

Patients who were initially screened with an IGRA

and who tested positive can be diagnosed right away with latent TB if they have no symptom/sign of active TB.

However, in Calgary, for refugee patients who were initially screened with a TST

and who tested positive, a follow-up IGRA is then usually performed in order to confirm the diagnosis of latent TB. This is because of the risk of false-positive TST results in the refugee population.

In Calgary, IGRAs (QuantiFERON-TB Gold) can only be ordered by TB Services, the Southern Alberta HIV Program, or the Calgary Refugee Health Program and will only be performed in certain laboratories. Therefore, these patients should be referred to TB Services using their

referral form.

LATENT TB TREATMENT

In Alberta, if the patient is diagnosed with latent TB, he/she will be offered treatment by TB Services. Shorter regimens are now the mainstay of treatment in Calgary. The main regimen is a 3 month course of daily self-administered isoniazid and rifampin. In patients at higher risk of hepatotoxicity, a 4 month course of daily rifampin is also an alternative.

Medications to treat latent TB are usually dispensed directly at TB Services (usually 1 month at a time). The TB specialist might send instructions to the family doctor regarding follow-up during treatment. Depending on the patient's age and risk factors, monthly liver function tests are usually recommended by the specialist. Compliance to latent TB treatment is often an issue in refugee patients and the family physician should play a role in monitoring adherence to treatment. Pill counts are probably the most reliable way to monitor compliance in this population.

During latent TB treatment, patients taking isoniazid

should also be asked periodically about symptoms of hepatitis. Patients on rifampin

should know that the drug typically causes an orange discoloration of bodily fluids. Also keep in mind that rifampin can interact with multiple other drugs.

Refer to the

Canadian Tuberculosis Standards for more information on the interpretation of TSTs and IGRAs, the advantages/disadvantages of both methods, and the management of latent and active TB.

POSITIVE

SYPHILIS SEROLOGY

CONFIRMATION TESTING

In Alberta, any positive syphilis enzyme immunoassay (EIA) screening test will be followed automatically by a Treponema pallidum

particule agglutination assay (TPPA) confirmation test and a Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR). A positive TPPA suggest either a current or past infection (it usually remains reactive for life). Any positive result should be discussed with AHS STI Centralized Services

(phone: 1-780-735-1466 or 1-888-535-1466). They will guide the physician through the recommended treatment depending on the case.

In the case of an isolated EIA result

(EIA+, TPPA-, RPR-), even if a false-positive is the most likely explanation, follow-up testing 2-3 weeks later is indicated to make sure it is not due to an early infection.

Refer to

Appendix A11 for the diagnostic algorithm

used at the Calgary Refugee Health Program for positive syphilis serology results. Recommendations may however vary depending on the province.

EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH SYPHILIS

All confirmed cases of syphilis should be met in person. They should be asked about any previous history of syphilis diagnosis or treatment. Physicians should counsel patients about syphilis transmission and inquire about recent sexual contacts. A full physical examination should be performed with a specific focus on the genital

(look for chancres, warts and regional lymphadenopathy), skin

(including palms and soles), neurological

(for signs of late neurosyphilis), and cardiac exams

(for tertiary syphilis). If not already done, the patient should also be screened for other sexually transmitted infections.

LATE LATENT SYPHILIS TREATMENT

Late latent syphilis is the most common form of syphilis diagnosed in refugee patients. Whereas primary, secondary and early latent syphilis infections are treated with a single dose of long-acting benzathine penicillin G 2.4 mu IM, late latent syphilis is treated with long-acting benzathine penicillin G 2.4 mu IM weekly for 3 consecutive weeks. Treatment should always be discussed with AHS STI Centralized Services.

Refer to the

Alberta Treatment Guidelines for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) in Adolescents and Adults 2018 for more information on the treatment of syphilis infections.